How to Write and Use Scala Functions That Have Multiple Parameter Groups

Scala lets you create functions that have multiple input parameter groups, like this:

def foo(a: Int, b: String)(c: Double)

Because I knew very little about FP when I first started working with Scala, I originally thought this was just some sort of syntactic nicety. But then I learned that one cool thing this does is that it enables you to write your own control structures. For instance, you can write your own while loop, and I show how to do that in this lesson.

Beyond that, the book Scala Puzzlers states that being able to declare multiple parameter groups gives you these additional benefits (some of which are advanced and I rarely use):

They let you have both implicit and non-implicit parameters

They facilitate type inference

A parameter in one group can use a parameter from a previous group as a default value

I demonstrate each of these features in this lesson, and show how multiple parameter groups are used to create partially-applied functions in the next lesson.

The goals of this lesson are:

Show how to write and use functions that have multiple input parameter groups

Demonstrate how this helps you create your own control structures, which in turn can help you write your own DSLs

Show some other potential benefits of using multiple input parameter groups

Writing functions with multiple parameter groups is simple. Instead of writing a “normal” add function with one parameter group like this:

def add(a: Int, b: Int, c: Int) = a + b + c

just put your function’s input parameters in different groups, with each group surrounded by parentheses:

def sum(a: Int)(b: Int)(c: Int) = a + b + c

After that, you can call sum like this:

scala> sum(1)(2)(3)

res0: Int = 6

That’s all there is to the basic technique. The rest of this lesson shows the advantages that come from using this approach.

Note that when you write sum with three input parameter groups like this, trying to call it with three parameters in one group won’t work:

scala> sum(1,2,3)

<console>:12: error: too many arguments for method

sum: (a: Int)(b: Int)(c: Int)Int

sum(1,2,3)

^

You must supply the input parameters in three separate input lists.

Another thing to note is that each parameter group can have multiple input parameters:

def doFoo(firstName: String, lastName: String)(age: Int) = ???

To show the kind of things you can do with multiple parameter groups, let’s build a control structure of our own. To do this, imagine for a moment that you don’t like the built-in Scala while loop — or maybe you want to add some functionality to it — so you want to create your own whilst loop, which you can use like this:

var i = 0

whilst (i < 5) {

println(i)

i += 1

}

Note: I use a

varfield here because I haven’t covered recursion yet.

A thing that your eyes will soon learn to see when looking at code like this is that whilst must be defined to have two parameter groups. The first parameter group is i < 5, which is the expression between the two parentheses. Note that this expression yields a Boolean value. Therefore, by looking at this code you know whilst must be defined so that it’s first parameter group is expecting a Boolean parameter of some sort.

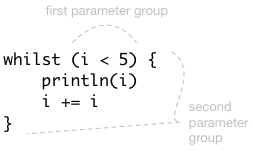

The second parameter group is the block of code enclosed in curly braces immediately after that. These two groups are highlighted in Figure [fig:twoParamGroups].

You’ll see this pattern a lot in Scala/FP code, so it helps to get used to it.

I demonstrate more examples in this chapter, but the lesson for the moment is that when you see code like this, you should think:

I see a function named

whilstthat has two parameter groupsThe first parameter group must evaluate to a

BooleanvalueThe second parameter group appears to return nothing (

Unit), because the last expression in the code block (i += 1) returns nothing

To create the whilst control structure, define it as a function that takes two parameter groups. As mentioned, the first parameter group must evaluate to a Boolean value, and the second group takes a block of code that evaluates to Unit; the user wants to run this block of code in a loop as long as the first parameter group evaluates to true.

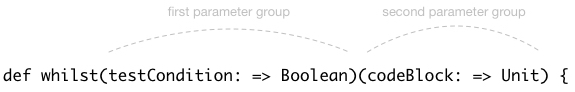

When I write functions these days, the first thing I like to do is sketch the function’s signature, and the previous paragraph tells me that whilst’s signature should look like this:

def whilst(testCondition: => Boolean)(codeBlock: => Unit) = ???

The two parameters groups are highlighted in Figure [fig:twoParamGroupsInWhilst].

Notice that both parameter groups use by-name parameters. The first parameter (testCondition) must be a by-name parameter because it specifies a test condition that will repeatedly be tested inside the function. If this wasn’t a by-name parameter, the i < 5 code shown here:

var i = 0

whilst (i < 5) ...

would immediately be translated by the compiler into this:

whilst (0 < 5) ...

and then that code would be further “optimized” into this:

whilst (true) ...

If this happens, the whilst function would receive true for its first parameter, and the loop will run forever. This would be bad.

But when testCondition is defined as a by-name parameter, the i < 5 test condition code block is passed into whilst without being evaluated, which is what we desire.

Using a by-name parameter in the last parameter group when creating control structures is a common pattern in Scala/FP. This is because as I just showed, a by-name parameter lets the consumer of your control structure pass in a block of code to solve their problem, typically enclosed in curly braces, like this:

customControlStructure(...) {

// custom code block here

...

...

}

So far, I showed that the whilst signature begins like this:

def whilst(testCondition: => Boolean)(codeBlock: => Unit) = ???

In FP, the proper way to implement whilst’s body is with recursion, but because I haven’t covered that yet, I’m going to cheat here and implement whilst with an inner while loop. Admittedly that’s some serious cheating, but for the purposes of this lesson I’m not really interested in the body of whilst; I’m interested in its signature, along with what this general approach lets you accomplish.

Therefore, having defined whilst’s signature, this is what whilst looks like as a wrapper around a while loop:

def whilst(testCondition: => Boolean)(codeBlock: => Unit) {

while (testCondition) {

codeBlock

}

}

Note that whilst doesn’t return anything. That’s implied by the current function signature, and you can make it more explicit by adding a Unit return type to the function signature:

def whilst(testCondition: => Boolean)(codeBlock: => Unit): Unit = {

--------

With that change, the final whilst function looks like this:

def whilst(testCondition: => Boolean)(codeBlock: => Unit): Unit = {

while (testCondition) {

codeBlock

}

}

Because I cheated with the function body, that’s all there is to writing whilst. Now you can use it anywhere you would use while. This is one possible example:

var i = 1

whilst(i < 5) {

println(i)

i += 1

}

The whilst example shows how to write a custom control structure using two parameter groups. It also shows a common pattern:

Use one or more parameter groups to break the input parameters into different “compartments”

Specifically define the parameter in the last parameter group as a by-name parameter so the function can accept a custom block of code

Control structures can have more than two parameter lists. As an exercise, imagine that you want to create a control structure that makes it easy to execute a condition if two test conditions are both true. Imagine the control structure is named ifBothTrue, and it will be used like this:

ifBothTrue(age > 18)(numAccidents == 0) {

println("Discount!")

}

Just by looking at that code, you should be able to answer these questions:

How many input parameter groups does

ifBothTruehave?What is the type of the first group?

What is the type of the second group?

What is the type of the third group?

Sketch the signature of the ifBothTrue function. Start by sketching only the function signature, as I did with the whilst example:

Once you’re confident that you have the correct function signature, sketch the function body here:

In this case, because ifBothTrue takes two test conditions followed by a block of code, and it doesn’t return anything, its signature looks like this:

def ifBothTrue(test1: => Boolean)(test2: => Boolean)(codeBlock: => Unit): Unit = ???

Because the code block should only be run if both test conditions are true, the complete function should be written like this:

def ifBothTrue(test1: => Boolean)(test2: => Boolean)(codeBlock: => Unit): Unit = {

if (test1 && test2) {

codeBlock

}

}

You can test ifBothTrue with code like this:

val age = 19

val numAccidents = 0

ifBothTrue(age > 18)(numAccidents == 0) { println("Discount!") }

This also works:

ifBothTrue(2 > 1)(3 > 2)(println("hello"))

One of my favorite uses of this technique is described in the book, Beginning Scala. In that book, David Pollak creates a using control structure that automatically calls the close method on an object you give it. Because it automatically calls close on the object you supply, a good example is using it with a database connection.

The using control structure lets you write clean database code like the following example, where the database connection conn is automatically close after the save call:

def saveStock(stock: Stock) {

using(MongoFactory.getConnection()) { conn =>

MongoFactory.getCollection(conn).save(buildMongoDbObject(stock))

}

}

In this example the variable conn comes from the MongoFactory.getConnection() method. conn is an instance of a MongoConnection, and the MongoConnection class defines close method, which is called automatically by using. (If MongoConnection did not have a close method, this code would not work.)

If you want to see how using is implemented, I describe it in my article, Using the using control structure from Beginning Scala

A nice benefit of multiple input parameter groups comes when you use them with implicit parameters. This can help to simplify code when a resource is needed, but passing that resource explicitly to a function makes the code harder to read.

To demonstrate how this works, here’s a function that uses multiple input parameter groups:

def printIntIfTrue(a: Int)(implicit b: Boolean) = if (b) println(a)

Notice that the Boolean in the second parameter group is tagged as an implicit value, but don’t worry about that just yet. For the moment, just note that if you paste this function into the REPL and then call it with an Int and a Boolean, it does what it looks like it should do, printing the Int when the Boolean is true:

scala> printIntIfTrue(42)(true)

42

Given that background, let’s see what that implicit keyword on the second parameter does for us.

Because b is defined as an implicit value in the last parameter group, if there is an implicit Boolean value in scope when printIntIfTrue is invoked, printIntIfTrue can use that Boolean without you having to explicitly provide it.

You can see how this works in the REPL. First, as an intentional error, try to call printIntIfTrue without a second parameter:

scala> printIntIfTrue(1)

<console>:12: error: could not find implicit value for parameter b: Boolean

printIntIfTrue(1)

^

Of course that fails because printIntIfTrue requires a Boolean value in its second parameter group. Next, let’s see what happens if we define a regular Boolean in the current scope:

scala> val boo = true

boo: Boolean = true

scala> printIntIfTrue(1)

<console>:12: error: could not find implicit value for parameter b: Boolean

printIntIfTrue(1)

^

Calling printIntIfTrue still fails, and the reason it fails is because there are no implicit Boolean values in scope when it’s called. Now note what happens when boo is defined as an implicit Boolean value and printIntIfTrue is called:

scala> implicit val boo = true

boo: Boolean = true

scala> printIntIfTrue(33)

33

printIntIfTrue works with only one parameter!

This works because:

The

Booleanparameter inprintIntIfTrue’s last parameter group is tagged with theimplicitkeywordboois declared to be an implicitBooleanvalue

The way this works is like this:

The Scala compiler knows that

printIntIfTrueis defined to have two parameter groups.It also knows that the second parameter group declares an implicit

Booleanparameter.When

printIntIfTrue(33)is called, only one parameter group is supplied.At this point Scala knows that one of two things must now be true. Either (a) there better be an implicit

Booleanvalue in the current scope, in which case Scala will use it as the second parameter, or (b) Scala will throw a compiler error.

Because boo is an implicit Boolean value and it’s in the current scope, the Scala compiler reaches out and automatically uses it as the input parameter for the second parameter group. That is, boo is used just as though it had been passed in explicitly.

If that code looks too “magical,” I’ll say two things about this technique:

It works really well in certain situations

Don’t overuse it, because when it’s used wrongly it makes code hard to understand and maintain (which is pretty much an anti-pattern)

An area where this technique works really well is when you need to refer to a shared resource several times, and you want to keep your code clean. For instance, if you need to reference a database connection several times in your code, using an implicit connection can clean up your code. It tends to be obvious that an implicit connection is hanging around, and of course database access code isn’t going to work without a connection.

A similar example is when you need an “execution context” in scope when you’re writing multi-threaded code with the Akka library. For example, with Akka you can create an implicit ActorSystem like this early in your code:

implicit val actorSystem = ActorSystem("FutureSystem")

Then, at one or more places later in your code you can create a Future like this, and the Future “just works”:

val future = Future {

1 + 1

}

The reason this Future works is because it is written to look for an implicit ExecutionContext. If you dig through the Akka source code you’ll see that Future’s apply method is written like this:

def apply [T] (body: => T)(implicit executor: ExecutionContext) ...

As that shows, the executor parameter in the last parameter group is an implicit value of the ExecutionContext type. Because an ActorSystem is an instance of an ExecutionContext, when you define the ActorSystem as being implicit, like this:

implicit val actorSystem = ActorSystem("FutureSystem")

--------

Future’s apply method can find it and “pull it in” automatically. This makes the Future code much more readable. If Future didn’t use an implicit value, each invocation of a new Future would have to look something like this:

val future = Future(actorSystem) {

code to run here ...

}

That’s not too bad with just one Future, but more complicated code is definitely cleaner without it repeatedly referencing the actorSystem.

If you’re new to Akka Actors, my article, A simple working Akka Futures example, explains everything I just wrote about actors, futures, execution contexts, and actor systems.

If you know what an ExecutionContext is, but don’t know what an ActorSystem is, it may help to know that you can also use an ExecutionContext as the implicit value in this example. So instead of using the ActorSystem as shown in the example, just create an implicit ExecutionContext, like this:

val pool = Executors.newCachedThreadPool()

implicit val ec = ExecutionContext.fromExecutorService(pool)

After that you can create a Future as before:

val future = Future { 1 + 1 }

The Scala language specification tells us these things about implicit parameters:

A method or constructor can have only one implicit parameter list, and it must be the last parameter list given

If there are several eligible arguments which match the implicit parameter’s type, a most specific one will be chosen using the rules of static overloading resolution

I’ll show some of what this means in the following “implicit parameter FAQs”.

No, you can’t. This code will not compile:

def printIntIfTrue(implicit a: Int)(implicit b: Boolean) = if (b) println(a)

The REPL shows the error message you’ll get:

scala> def printIntIfTrue(implicit a: Int)(implicit b: Boolean) = if (b) println(a)

<console>:1: error: '=' expected but '(' found.

def printIntIfTrue(implicit a: Int)(implicit b: Boolean) = if (b) println(a)

^

Yes. This code, with an implicit in the first list, won’t compile:

def printIntIfTrue(implicit b: Boolean)(a: Int) = if (b) println(a)

The REPL shows the compiler error:

scala> def printIntIfTrue(implicit b: Boolean)(a: Int) = if (b) println(a)

<console>:1: error: '=' expected but '(' found.

def printIntIfTrue(implicit b: Boolean)(a: Int) = if (b) println(a)

^

In theory, as the Specification states, “a most specific one will be chosen using the rules of static overloading resolution.” In practice, if you find that you’re getting anywhere near this situation, I wouldn’t use implicit parameters.

A simple way to show how this fails is with this series of expressions:

def printIntIfTrue(a: Int)(implicit b: Boolean) = if (b) println(a)

implicit val x = true

implicit val y = false

printIntIfTrue(42)

When you get to that last expression, can you guess what will happen?

What happens is that the compiler has no idea which Boolean should be used as the implicit parameter, so it bails out with this error message:

scala> printIntIfTrue(42)

<console>:14: error: ambiguous implicit values:

both value x of type => Boolean

and value y of type => Boolean

match expected type Boolean

printIntIfTrue(42)

^

This is a simple example of how using implicit parameters can create a problem.

If you want to see a more complicated example of how implicit parameters can create a problem, read this section. Otherwise, feel free to skip to the next section.

Here’s another example that should provide fair warning about using this technique. Given (a) the following trait and classes:

trait Animal

class Person(name: String) extends Animal {

override def toString = "Person"

}

class Employee(name: String) extends Person(name) {

override def toString = "Employee"

}

(b) define a method that uses an implicit Person parameter:

// uses an `implicit` Person value

def printPerson(b: Boolean)(implicit p: Person) = if (b) println(p)

and then (c) create implicit instances of a Person and an Employee:

implicit val p = new Person("person")

implicit val e = new Employee("employee")

Given that setup, and knowing that “a most specific one (implicit instance) will be chosen using the rules of static overloading resolution,” what would you expect this statement to print?:

printPerson(true)

If you guessed Employee, pat yourself on the back:

scala> printPerson(true)

Employee

(I didn’t guess Employee.)

If you know the rules of “static overloading resolution” better than I do, what do you think will happen if you add this code to the existing scope:

class Employer(name: String) extends Person(name) {

override def toString = "Employer"

}

implicit val r = new Employer("employer")

and then try this again:

printPerson(true)

If you said that the compiler would refuse to participate in this situation, you are correct:

scala> printPerson(true)

<console>:19: error: ambiguous implicit values:

both value e of type => Employee

and value r of type => Employer

match expected type Person

printPerson(true)

^

As a summary, I think this technique works great when there’s only one implicit value in scope that can possibly match the implicit parameter. If you try to use this with multiple implicit parameters in scope, you really need to understand the rules of application. (And I further suggest that once you get away from your code for a while, you’ll eventually forget those rules, and the code will be hard to maintain. This is nobody’s goal).

As the Scala Puzzlers book notes, you can supply default values for input parameters when using multiple parameter groups, in a manner similar to using one parameter group. Here I specify default values for the parameters a and b:

scala> def f2(a: Int = 1)(b: Int = 2) = { a + b }

f2: (a: Int)(b: Int)Int

That part is easy, but the “magic” in this recipe is knowing that you need to supply empty parentheses when you want to use the default values:

scala> f2()()

res0: Int = 3

scala> f2(10)()

res1: Int = 12

scala> f2()(10)

res2: Int = 11

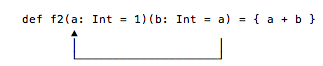

As the Puzzlers book also notes, a parameter in the second parameter group can use a parameter from the first parameter group as a default value. In this next example I assign a to be the default value for the parameter b:

def f2(a: Int = 1)(b: Int = a) = { a + b }

Figure [fig:multParamGroupsDefValues] makes this more clear.

The REPL shows that this works as expected:

scala> def f2(a: Int = 1)(b: Int = a) = { a + b }

f2: (a: Int)(b: Int)Int

scala> f2()()

res0: Int = 2

I haven’t had a need for these techniques yet, but in case you ever need them, there you go.

In this lesson I covered the following:

I showed how to write functions that have multiple input parameter groups.

I showed how to call functions that have multiple input parameter groups.

I showed to write your own control structures, such as

whilstandifBothTrue. The keys to this are (a) using multiple parameter groups and (b) accepting a block of code as a by-name parameter in the last parameter group.I showed how to use

implicitparameters, and possible pitfalls of using them.I showed how to use default values with multiple parameter groups.

The next lesson expands on this lesson by showing what “Currying” is, and by showing how multiple parameter groups work with partially-applied functions.

My article, Using the

usingcontrol structure from Beginning ScalaJoshua Suereth’s scala-arm project is similar to the

usingcontrol structureThe Scala “Breaks” control structure is created using the techniques shown in this lesson, and I describe it in my article, How to use break and continue in Scala